This is the story of the Monk Family who lived in Shenley Road Camberwell in south-east London and is told by Kathleen.

Doreen, Daisy & Kathleen Parker

Doreen, Daisy & Kathleen Parker

I was born on the 13th September 1924 and at that time my parents — Frank and Daisy had had three other children, two still living and one who had died. My sister Winnie was 3 at the time of my birth and Leslie was 2. The baby who died was Leslie’s twin who had lived a very short time. Our other sister Doreen was born in February 1927 and another brother Frank lived only a few weeks after his birth in 1929.

We were all born at home with the assistance of someone we called ‘the old nurse’. She lived above the barbers shop in Vestry Road and when she was needed one of us went to fetch her. I only remember her as being very old, short and wearing a white overall over a black dress.

My father was a lot older than my mother — when Doreen was born. Mum was 41 and Dad was 65. He had a grown up family with his first wife who had died. They were more or less the same age as Mum and tended to try to take over the care of the children. For instance, once a week Ada would come over straight from work for her tea (she was unmarried) and she always had a boiled egg. Afterwards she would wash our hair each one in turn but we never knew why she did this and we never asked.

Ada lived with my other step-sister in Footscray Road, Eltham. Florrie was married to Ernest and they had a son, Alfred. They had had another child but we never knew him. Dad’s other son was Albert – known as Bert – and he lived at Charlton almost next door to the tram depot. He and his wife Ethel had three children. The eldest was Wilfred, and then Ronald and lastly Gladys. We didn’t see very much of them but we did visit Florrie quite often and we would get the tram to Eltham and then a bus to her house. She was a dressmaker and made us several dresses – all mostly straight up and down – no shape – and all the same.

The Monk family in full force, 1945. In the garden of Shenley Road.

The Monk family in full force, 1945. In the garden of Shenley Road.

Dad had worked for the London Passenger Transport Board (the LPTB) and when we were young he was based in Peckham at Basing Road. I think he was there just working out his retirement. Les sometimes had to take his food down to him during his lunch break from school. It was quite a distance and meant he had to run both ways to get back in time to eat and then back to school.

Dad was a very strict Victorian Father and if you were told to do something you did it – no arguing. All our meals had to be eaten – nothing could be left – and this was very difficult when it came to the ‘greens’. In those days they were over-cooked and not very pleasant but we were not allowed to leave the table until every scrap had gone. Mum was much more lenient and if Dad had his meal in the front room or left the table early she would quickly get rid of them for us.

There was very little money to spare so we didn’t get pocket money. Ada used to give us a penny a week but we were not allowed to spend it. It was put away towards our fare for our annual holiday at Ashford and if there was any money over it went to help pay for the battery for the wireless that Ada bought for us all.

The wireless had an accumulator, which had to be charged every so often. We were given the job of taking it round to the shoe repairers who was some reason charged them. It was quite a dangerous assignment as it was full of acid and we used to go on our skates.

I think Mum had quite a hard life but we had a happy childhood. There were eleven people living in the house — 6 of us and 5 of the Castles who lived upstairs. There was Mr and Mrs Castle and 2 sons and a daughter. All of them, with the exception of Mrs Castle, worked at Samuel Jones the paper manufacturers in Peckham. As there was only one toilet in the house you can imagine how difficult it was in the morning, when they were trying to get to work and we were trying to get to school! Somehow we managed it - but at times there were complaints all round. There wasn’t a light in the toilet so you had to take a torch or a candle. We always went two at a time because it was dark up there and one had to stand outside for company as we were frightened on our own. The toilet paper was cut up newspaper and it wasn't very soft.

When Mum did the washing she had to fill the copper first and then light the fire underneath and wait until the water was very hot. Then she would transfer enough water into the sink and put the rest into a bath to use for rinsing. She would fill the copper again with cold water and when she had washed the white sheets and pillowcases, towels, tea towels etc. she would put them in the copper to boil

After she had rinsed everything they had to go through the wringer which was a very big, heavy thing with wooden rollers, so that she could get most of the water out. Then the clothes would be hung out in the garden to dry and later on they would be ironed. In the winter we would put 4 irons on the top of the fire to heat (it was something like an Aga but no where near as useful or as smart). It had to be black-leaded every week.

In summer the irons would be put on a gas ring to heat. Once hot they would be rubbed on a bar of soap to make them smooth. We children had our own jobs to do. Les had to help Dad mend the shoes and also to clean them. As a treat Doreen and I were allowed at times to try to match the sole patterns to the shoes Dad was going to mend. Then he would put the pattern on a length of leather and cut it out. After soaking the leather he would nail it to the shoe and then he would heel-ball them to make the edges of the leather the same colour as the shoes.

The rest of us had to clean the silver and polish the brass, hearthstone the doorstep and wash the tiles and also black-lead the coal hole.

Dad suffered from Bronchitis and didn't go out very much just used to sit in his chair. He died in 1938 and was buried in the Old Cemetery at Forest Hill. He was buried in the same grave as his first wife. Doreen and I were sent to stay with Aunt Cissie whilst Dad was lying in his coffin in the front room and on the day of the funeral we went to stay with Auntie Cissie's son and daughter in law for a couple of days at Broad Walk. This was quite an eye-opener for us - we had a bedroom with an electric fire set in the wall and a bathroom with lots of hot water and fires in every room also carpets - and they had a car. Wyn wasn't so lucky - she had to get up in the night to make sure that Dad hadn't got out of his coffin as Mum thought she heard him walking around. Mum received £20 from Dad's insurance and she spent it on a settee and a lovely rug. We did feel posh.

At this time Doreen and I were both at Peckham Central School and I was learning shorthand-typing and bookkeeping to prepare me for an office job. Wyn was working up in London and Les was with the car section of The Service Company. As we had very little money Mum had to go to work and she joined her sister - Auntie Bessie - at Elders and Fyffes as a cleaner. It was very hard work as most of the floors were rubber. They went out early morning about 6am and worked until about 9am, then went back at 6pm to 8pm.

Stuart Brown (left) and Lesley Monk.

Stuart Brown (left) and Lesley Monk.

About 2 weeks before war was declared Doreen and I went on holiday with a teacher from the boys school Lyndhurst Grove where Les had been taught. His name was Mr Maynard and we all, including Mum, knew him very well. He was going on holiday to Sturminster Newton in Dorset to stay on a farm where he and his wife had been on holiday for years. His wife was now an invalid and didn't want to go. It seems quite peculiar in this day and age but no one seemed to worry then.

I think he took us for company and also perhaps because he was sorry for us, as he knew we wouldn't have a holiday. Anyway Doreen and I had a smashing time, we went to Stonehenge and to Salisbury and we also helped on the farm. Sadly our holiday was cut short as all teachers were recalled to help to prepare for the children evacuation should the war come. Mum decided we should go down to Ashford to finish our holiday and the war started when we were there.

We had gone for a walk through the fields with Joan Burton and a friend of hers whilst Aunt Lucy, Mum and Uncle Jack had gone to Church. We were right out in the country when the sirens went - we met some people who told us to get home as soon as possible as we were at war with Germany and it looked as though they were going to bomb us. We ran all the way and just as we reached home the all-clear went. It was a false alarm.

Anyway Ashford was where we stayed for the next nine months only going home once at Christmas but Mum had to go home the next day. I quite enjoyed being there as the lessons were quite easy and I became a prefect but Doreen wasn't happy, she missed Mum too much so she made my life difficult at school by not behaving properly and I had to sing her to sleep each night. Auntie Lucy made us work quite hard, cleaning windows - doing our own washing and all the washing up but we survived.

We had been going home in May because there hadn't been any air raids on London in fact there had been a few near Ashford. However our Headmistress was told by the education authorities that we should not return and when she 'phoned Mum she said we were to stay. This upset Doreen very much and she was very unhappy. However fate took a hand as they evacuated Dunkirk. This meant the troop trains coming through Ashford and most of them stopped and we used to give them tea and food and talk to them. They looked absolutely shattered and tired out. They gave us coins, mostly French, and thanked us. After Dunkirk they decided to evacuate Ashford so Doreen and I came home. It was time for me to leave school and Doreen wanted to be home so we came back to London in time for the Blitz.

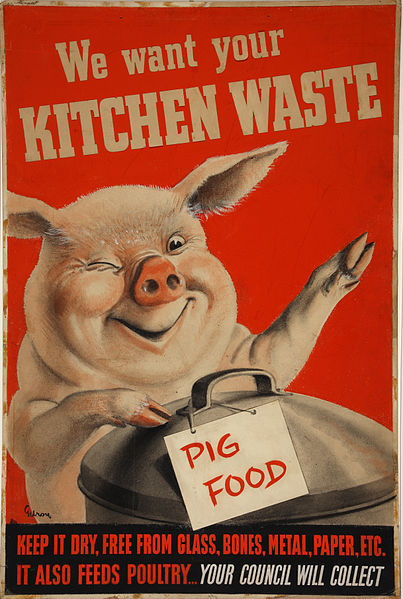

You can imagine what happened. Sometimes it overflowed and the smell and the flies were awful and you wondered - if you ever had a chance - whether you would fancy a piece of pork.

As I now had to find work Mum and I went up to the Snow Hill Labour Exchange to see if they had any vacancies for a school leaver. This was a special exchange for people who wanted office work. They sent me for an interview to The International News Company in Breams Buildings which ran between Fetter Lane and Chancery Lane. They were Importers of American magazines and exporters of English. I was interviewed by Mr Lutz who was the Managing Director. He was a very nice man and he said that if my references were O.K. I could have the job at £1 a week which was a very good wage in those days.

At this time Doreen had to go back to school. There were not many schools open as so many of the pupils had been evacuated, however she went back to Peckham Central (our old school) and tried to get on with her education. They couldn't go to school all day and every day but the teachers did their best. Les and his friends had now been posted and only Stuart stayed with him. They were in the Royal Artillery and were stationed in Danson Park. This was very near Ivy and Fred and she very kindly allowed them to have a bath at her place every week and also invited them for a Saturday meal. Wyn was working in Jones and Higgins at the corner of Rye Lane in Peckham. She was in the fashion department and sold coats and dresses etc.

The Blitz started on Saturday the 7th of September 1940. My air raid warning had gone and then the German Planes started to appear and in amongst them were the R.A.F. fighters. It was all new to us and we just stood out in the street and watched. It seemed very exciting and we didn't appreciate what was happening The bombers went over us and dropped some of their bombs on the Woolwich Arsenal. That was very dangerous as there were cases of nitroglycerine and live ammunition there. It look 200 pump engines to contain it.

In the morning we all staggered forth not knowing what we would find. We did this for the first few nights and then decided we would be better indoors in the cellar.

The cellar had always been a worry to us because you had to go downstairs before you could light the gas and as there were mice down there we used to bang on the walls before venturing down. However we had been very fortunate that several people in our road wanted to have electricity put on and as we were in that area we got ours done free. This was also a blessing as the radio we were given came from a main source. We only got two programmes but it used to inform us when an air raid warning for the London area had been officially notified and also when the all-clear had been given.

We never fully undressed but put some comfortable clothes on and always took our handbags and insurance policies down there with us, just in case we had to evacuate. On that first Saturday there were 430 Eastenders killed and on the Sunday 412 and the Monday night 370. That was without all the injured and those that were made homeless. The siren would go about 6-7pm each night and sometimes Mum and Auntie Bessie would be just finishing work. They often found it difficult to get a bus but so many motorists - mostly business vans used to give people lifts. I often went to work this way but mostly managed a bus or tram to come home.

We didn't only have night raids we had them in the daytime too. Our firm didn't have an air raid shelter so the Daily Mirror (which was almost opposite us) allowed us to use theirs. Sometimes these raids went on for a very long time and we were losing a lot of work time so our boss decided we could only go to the shelter when the imminent danger warning was given. Then we had to run like hell across the road.

As the day raids continued we stopped going over to the shelter but went down into our own basement. It wasn't all that safe as it was mostly wood and with all the newsprint and books we could have been in difficulty. The raids never seemed quite so bad in the daytime but night was a different thing. You had to rush your meal and clear up before the siren and then down to the cellar - we used to play games down there - such as monopoly, that's why I never want to play it now. Of course we read as well and did various other tasks but it was very difficult to concentrate with the noise of the guns, the aeroplanes and then the bombs.

When they dropped the bombs it was always a stick of them, about 8 or 10 and each one seemed to come nearer to you and I can tell you it was absolutely terrifying. One of the nearest to us blew all the windows out and the folding doors were forced open and Mother's china cabinet fell over. She had a beautiful dinner and tea service in it which we never used and it was all broken. The only things left were two ugly decanters which no one liked. Apart from the high explosive bombs there were also incendiaries (we had a bucket of sand to put those out) delayed action bombs and land mines. The latter two were the worst as we had to wait for the army to come and defuse them. If there had been a lot of these we often had to leave home until they could be dealt with.

Often the bombs would hit the water mains or the electric and gas mains so they would open a standpipe and we would go and collect water. Auntie Cissie had a coal range and if we didn't have any gas to cook by we used to take our food up to her and she would cook it on the range.

On my birthday September 13th 1940 we had an early day raid and they dropped a stick of bombs which started at the bottom of our road in the main Peckham Road. Each bomb came a bit nearer but we were very fortunate they didn't reach us but they hit our friend's house 7 doors away. Joan was in her kitchen which had a tin roof - it was an extension - and fortunately for her it came down in one piece and she was sheltered by it. She came up to our house with a few of the things she had left and we washed her hair about 6 times but we couldn't get all the dust etc out of it. She only stayed the one night with us and then went to stay with her grandparents. One of our other friends wasn't so lucky, her house was completely demolished and she was killed.

Mum was very nervous being home on her own during the day as the Smiths had moved out. Mr Smith had been called up and his wife had decided to go and live elsewhere. One afternoon the siren went and Mum rushed up the road to be with her sisters but the planes came over and started dropping their bombs. The air raid warden told her to take cover but she thought she would be O.K. however the bomb blast caught her and blew her round the corner. They picked her up and she said she was alright but her nerves were bad after that.

Les was now stationed on Clapham Common. He had been promoted to a bombardier and was in charge of the cookhouse (goodness knows why). This meant that he still had to man the guns and also look after the cooking. He and the other cooks had to go from the heat of the kitchen out to the cold of the gun site when there was a raid. One night whilst on the guns he was hit in the back by a shell and was taken to the Womens Hospital at Clapham Common. Because of continuously going from the heat to the cold he was very run down and consequently got pneumonia. He was very ill and his lungs were affected and they thought he had T.B. He was transferred to Epsom and after having a lot of tests they altered the diagnosis to emphysema. He had a tube put through his back into both lungs to drain them and was wrapped completely round with cotton wool and bandages.

He was told to be very careful not to get hit in the back as the tubes could pierce his lungs. He used to walk around with his arm behind his back for protection. He was eventually discharged from the army in 1943 and given a pension and he also had a disabled badge to wear but he hated going out because he looked reasonably well and people wondered why he wasn't in the forces. Whilst in hospital in Epsom he was nursed by Doris and they spent time with each other and eventually got married. At the same time as Les was in hospital, Doreen was taken ill. We had gone to a party at a friends and she hadn't felt too well so laid on the settee. Unfortunately there was an air raid so we couldn't come home until it was over. We had a very difficult time getting her home as she could hardly walk because of the pain.

When we got home we sent for the doctor and he immediately called an ambulance and took her to St. Giles Hospital – she had appendicitis. They said they were un able to operate there because of bomb damage so she was transferred to Dulwich Hospital where they operated, so we were then visiting two hospitals.

We all went our separate ways from there and I crossed over into Farringdon Street to go through the narrow passage that took me to Breams Buildings. When I had walked through it last it had consisted of two rows of small houses-perhaps about 10 each side of the alley with small gardens. I was unable to travel this way this time as not one house was standing they were completely destroyed it was quite horrific and I prayed that they had all been in a shelter somewhere.

The raids went on for 78 consecutive nights and days and we wondered if they would ever stop. One night before Les was injured a friend of his came to visit- Peggy- and when it was time for her to go there was a raid on. So Les and another friend and I walked her home. It took about half an hour each way and it was one of the most frightening times I had -because the guns were firing all the time- there was so much shrapnel falling and you could hear it and see it. It was very hot and very sharp and could have injured us badly. It was alright for Les, he had his tin hat with him. I tried not to do anything like that again. Another time we went to Waterloo Station to see one of our friends off on a train. An air raid started and so we went down the tube for shelter-never again-it was full of people but it wasn't that which worried us it was the fact that we didn't know what was happening and we found that more frightening that actually hearing everything.

Whilst in the Theatre the air raid warning went and we were told that if we wished we could leave but the show would go on. We decided to stay as did a lot of people but it's rather difficult to concentrate when there are guns going and bombs dropping. However we enjoyed it even though walking home up a dark Shenley Road we almost walked into Mr Rose.

There were quite a few funny times during the blitz like when we sat with candles because the electric had gone only to find that it just needed a shilling in the meter. Another time we were sitting in the front room and the bombs started falling so we got on the floor. Mum somehow got her head under the piano stool and everytime the bomb dropped she jumped and the stool jumped with her right across the room. There were so many things to laugh at but I can't remember them-it wasn't all being frightened and upset.

They were supposed to come at 11 o'clock on Christmas morning. As food was on ration we didn't have a great selection but we did have a Christmas pudding (only small but better than nothing). When our visitors arrived Earl was there but the other soldier was different-he was Jack Westine and that turned out to be a very lucky day because he became like a brother to us and spent all his leaves at our house and also introduced his brother-in-law-who was in the Canadian Air Force-and he too spent time with us.

However getting back to Christmas. Wyn, being worried about her two sisters meeting Canadians, had managed to get some leave and arrived home just as we sat down to dinner. Being her usual tactful self she told them that they had Canadians near where she was posted and she didn't think much of them. They didn't get too upset about it as they had to try and get the pudding out of the saucepan as the basin had got fixed in. Eventually all worked out well and they came back the next day and continued until they were sent home.

Soon after this we moved up to Aunt Cissie's, her lodgers had left so she and Aunt Bessie moved upstairs and we had their flat. There was more room for us as we had two rooms and a kitchen and scullery downstairs and at the top of the house we had two bedrooms under the eves. There was only one difficulty here as we used to have to wash in the scullery (we still didn't have a bathroom) and besides the sink there was the copper-for the hot water- and also the gas stove. Auntie Cissie always had to do things at certain times and one of them was brushing the mats in the morning. When either Doreen or I were washing she would come through to go into the garden with the mats under her arm and as she went past us she would knock us and also hit the gas taps and turn the gas on. It was a source of great annoyance to us.

With the daily blitz finished life became easier although when we did get a raid it seemed more frightening especially as Auntie Cissie didn't have a cellar like 75 but just stairs down into the coal hole. We used to sit on the stairs and hope that the staircase would protect us. When Les came out of hospital they gave him a Morrison shelter. It was put into the back room and was made of steel and looked like a huge table. It was about the height of a table and had mesh sides to it. One side was against the wall and we had to crawl into it. If you were first one in you were right up against the wall and you couldn't sit up or move. We only used it when the raid was really bad. It was very claustrophobic and I think this is why neither Wyn or Les would go into a lift or an enclosed space. Wyn still won't.

The war hadn't been going too well, we had lost Singapore and many other places in the far east. After Montgomery took over the 8th Army things began to get better in North Africa but there was no end in sight. We were quite heavily rationed during the war and for several years after in fact when Eric and I were married in 1953 we still had to have ration books. Our allowances were 2oz butter and 4oz sugar a week, 2oz cheese, 4oz margarine, one egg if we were lucky and a couple of rashers of bacon. We had 2ozs of tea and sometimes we had coffee but it was camp coffee in a bottle-not any grains-and it looked and tasted like meat browning.

At one time bread and potatoes were also rationed and there wasn't a lot of fruit around. In fact most children didn't see a banana until the war was over. Our sweets were on ration as well. 4ozs a week and there wasn't much chocolate. Then clothes went on coupons so we couldn't renew much of our wardrobe. Nylons hadn't made their appearance in our part of the world until the Americans arrived and you had to be friendly with a soldier to get those. We often did not have any stockings so we used to paint our legs with the above mentioned gravy mixture and then pencil a line down the back to look like a seam (very elegant) Of course we didn't have tights either. Every lunch hour we would go round the shops -especially Walworths- to see if they had received any make up etc. which was in short supply. There was one good thing about the rationing, you didn't put on weight.

To my mind the worst food we had was dried egg! It was a vivid yellow colour and unless you could find something to flavour it tasted awful. Although I must mention that some people did like it. As a very special treat we might find a tin of Spam from America and that was really good. Kennedy's used to make their own sausages and meat and fish paste and if the word went round that they had sausages it was a great rush to get in the queue. They weren't on our ration books but they tended to distribute them according to how many ration books you had. Which I suppose was only fair. When the Canadians came to stay or Wyn was home on leave they would bring their ration cards with them which helped a lot.

One day as I was on my way home from work I turned the corner from Chancery Lane into Fleet Street and met Bob face to face. I asked him why he never visited us and he said he didn't think he would be welcome. I told him that was silly and for him to come the next day, which he did and from then on he came every leave - especially when he and Wyn got together. It came as quite a surprise when this happened as they were both in the services and couldn't always get their leave together and Wyn was a great one for falling asleep in front of the fire when it was near her bedtime. We used to go to bed and hope that she would stay awake long enough to manage at least a conversation with Bob. She must have managed O.K. as when he was sent back to Canada before the end of the war she was engaged to him. The second front started on June 6th 1944 and on that day I was in Somerset with my friend Nellie. We were staying with her Aunt and Uncle in Frome for a week.

On the day the invasion started we were lying in a field and we watched in amazement as it seemed thousands of gliders passed over head and many aeroplanes. It was an exciting time but the allied forces had a very hard and bloody fight to get a foothold on French soil but eventually all the bridgeheads were captured. Jack Brooks went over on D. Day but was back within a week as he was injured and he wasn't sorry to be out of it.

Just when we thought things were going reasonably well Hitler gave us another shock. I was staying with Dorothy at Shooters Hill for a few days and we were in bed when suddenly the guns opened fire. There was no sound of plane engines but when I looked out of the window I saw a small plane which looked as though it was on fire. I rushed to the other side of the house and saw that there was indeed flames coming out the back of it. Dorothy and I watched it and suddenly the engine cut and it dived to earth and when it hit there was a massive explosion.

So started the V1 or the buzz bombs or flying bombs whichever you wanted to call them. One of the first to fall happened at Nunhead and the damage was horrific and there were many dead and injured. At first the fighters could not shoot them down and neither could the guns but the barrage balloons managed to trap some. However eventually the pilots managed to use their wings to tip the bombs so they didn't make it to London but fell (they hoped) in the fields.

In some ways the flying bombs were not as traumatic as an ordinary bombing because you could hear and see them and you knew as long as the engine was working you were safe. One night I was waiting for a tram on Blackfriars Bridge to take me home from work when one came over, we all stood and watched it but for that moment we were safe as it cut out a little way from us. We watched it came down and explode and we thought of all the people who had been killed and injured by it.

Another evening I had reached Camberwell Green and was walking the rest of the way home when one came down. Another girl and I rushed into a chemist shop and knelt on the floor and it wasn't until it had exploded away from us that we realised we had been kneeling in front of a glass cabinet, that would have done us a lot of good if the blast had affected the shop. I continued walking home and another one started to come down. This time I went into the greengrocers and he said "don't worry the Lord will take care of you" and I answered him "well he hasn't taken care of those that have just been hit". When I came out of the shop I could see the dust and smoke rising and it was near my home. I rushed along and found they had actually hit some flats and St Giles Hospital. Fortunately for Mum and the Aunts but not for the people concerned.

That was one of the worst parts of the raids and the buzz bombs that you never knew when you went to work in the morning whether you would have any family or home when you left work or whether you would actually get home again. The firm I worked for was hit but fortunately on a Sunday when there was no one there. Signodes next door wasn't too bad so they allowed us to have part of their premises so we could carry on.

Our cousin Victor who was a flight engineer in the R.A.F. had been on leave at Preston with his Mother and came back just as the second front started. He sadly was shot down over Gelsenkirchen six days after, on a bombing raid. The sad thing was that his Mother did not know he was aircrew and he never wore his wings when he went home. So when she received the telegram saying that he was missing believed killed she was devastated. Les and I knew he was flying and it was bad enough for us but for her, her only son, it was shattering. He was a really nice person and we all miss him.

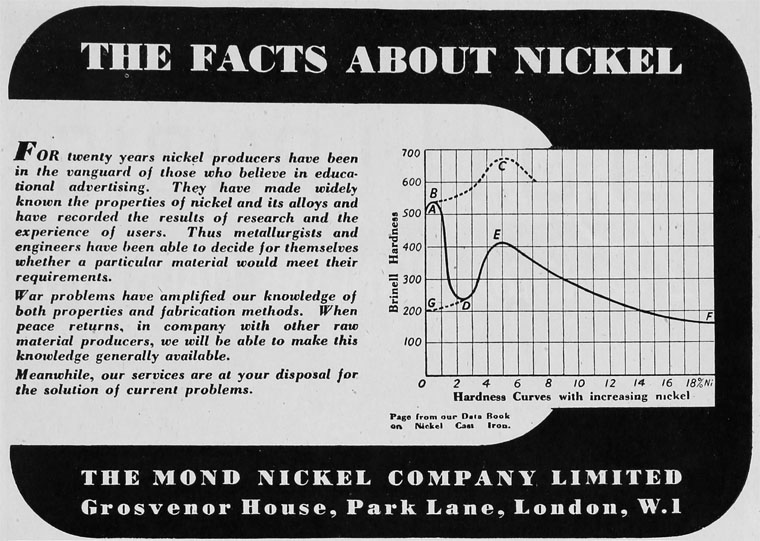

At this time Les had gone back to work for the Service Company with Eric's Father and they were running the photographic shop. They were in a small shop near Chancery Lane in Holborn but a bomb damaged that and they moved to larger premises near Grays Inn Road but still in Holborn.

We were all carrying on working and dodging the flying bombs as best we could. These raids lasted for 10 weeks and in that time 48,000 people were killed. Just when we thought we wouldn't need to worry over raids and could go about in safety Hitler launched his final weapon-the V2 rocket. These could not be heard at all until they hit the ground and exploded. On November 25th 1944 the 251st V2 fell at New Cross and Woolworths and The Co-operative completely disappeared. There were 171 people killed and 120 seriously injured. It was a terrible sight. I was at work at the time and talking to my friend on the telephone who was at Lewisham. We both heard the explosion and I thought it was in the city near me but she could see the smoke and dust rising up and told me it was New Cross.

This was one of the worst incidents but there were so many more. The last rocket fell in March 1945 at Orpington. The R.A.F. had been bombing Piedenunder where the V1 and V2 were launched and with the invasion of France and then the Low Countries and Germany the sites had been taken by the Allies and it really was the end of the bombing.

By the time we got home again none of us were really sober. Mum couldn't manage to dish up the dinner and Doreen in particular couldn't find out how to pierce the potatoes with her fork and we ended up laughing too much to eat. We were assisted up the stairs to our beds and both of us slept until 3pm when the prime minister spoke. That was the first and last time either of us was drunk.

When we had been told officially that the war was over we started our celebrations. Someone brought their piano out into the street and we lit a huge bonfire. People supplied food and drink and we sang and danced the night away. We did go for a walk round the neighbouring streets and enjoyed all the fun and games there. It is hard to explain the relief and joy of knowing that our loved ones would now be safe from fighting and that we would not have any more air raids. The next day we all went up to the Mall and walked down to Buckingham Palace to see the King and Queen and the Princesses who came out on to the balcony.

You cannot imagine what a wonderful feeling it was to know that you could travel around and sleep in your own bed without wondering whether the air raid siren would go and there would be bombs or rockets etc to frighten you. Of course the war was still going on in the far east - fighting the Japanese - and we were still losing a lot of soldiers and so many many families could not celebrate properly for worrying about their relatives.

The men in Burma were often called the forgotten army as the people at home really took the war in Germany as the one that affected them most. The 14th army had a terrible time in Burma and any prisoners of war taken by the Japanese knew they would be ill-treated and made to work on the railway. When they were liberated most of them were in a similar condition to the people held in the camps in Germany.

The Americans decided to try to end the war quickly and as the Japanese would not surrender it was agreed to drop the atom bomb. This was a dreadful thing and they dropped one on Hiroshima and one on Nagasaki. They killed so many people and thousands were affected by the fall out and died terrible deaths for many years to come. Whether it was the right thing to do has been discussed for years but it certainly saved so many lives of Australian-New Zealanders-British-Canadians -American and several other nationalities soldiers, sailors and airmen- not forgetting all the prisoners both civilian and military.

The end came in August and at last all the forces could relax and look forward to their return home.

We had a lot to be thankful for and this month we have at last paid back the Americans for the lease-lend they supplied us with. Perhaps if we had lost the war we would have been helped to rebuild our country and supplied with food and materials but then we didn't want that.

The Channel Islands-Jersey-Guernsey-and the other smaller islands which had been occupied by the German Army were liberated on May 9 1945 and it was a wonderful day for them.

Dedicated to the memory of Kathleen Parker, 1924–2019.

Digitised by Alasdair Monk with research & proofreading by Esra Gökgöz.

Rye Lane, Peckham circa 1925.

Rye Lane, Peckham circa 1925.

Archive footage of summer time in Folkestone, 1931.

Archive footage of summer time in Folkestone, 1931.

Samuel Jones & Co. advertisement.

Samuel Jones & Co. advertisement.

Double Deck 'Pullman' service through Kingsway tramway tunnel inaugurated by the L.C.C. 1931.

Double Deck 'Pullman' service through Kingsway tramway tunnel inaugurated by the L.C.C. 1931.

Footage of the territorial army on manoeuvres, 1939.

Footage of the territorial army on manoeuvres, 1939.

'We want your kitchen waste'. UK government poster produced between 1939 & 1946.

'We want your kitchen waste'. UK government poster produced between 1939 & 1946.

The facade of the International News Company building, Breams Buildings, where Kath worked. Photo circa 1889.

The facade of the International News Company building, Breams Buildings, where Kath worked. Photo circa 1889.

An Anderson shelter in use.

An Anderson shelter in use.

A bomb-damaged Elephant and Castle, circa 1940.

A bomb-damaged Elephant and Castle, circa 1940.

Firemen on Ludgate Hill.

Firemen on Ludgate Hill.

The Stoll Theatre at 22 Kingsway was built as a rival to the Royal Opera House London. It was demolished in the 1960s to make way for office buildings. Photo circa 1911.

The Stoll Theatre at 22 Kingsway was built as a rival to the Royal Opera House London. It was demolished in the 1960s to make way for office buildings. Photo circa 1911.

A sign at a Red Cross Club reads 'Spend your Xmas at home with a British Family'.

A sign at a Red Cross Club reads 'Spend your Xmas at home with a British Family'.

An advertisement for The Mond Nickel Company, November 1944.

An advertisement for The Mond Nickel Company, November 1944.

Churchill announces Germany's unconditional surrender.

Churchill announces Germany's unconditional surrender.

Men and women dance the conga around a bonfire in East Acton, London during the evening of VE Day, 8 May 1945.

Men and women dance the conga around a bonfire in East Acton, London during the evening of VE Day, 8 May 1945.

Rubble and burnt out buildings surround St Paul's Cathedral, September 1940.

Rubble and burnt out buildings surround St Paul's Cathedral, September 1940.